This proposal was a finalist in the Northern Avenue Bridge Ideas Competition, an initiative by the City of Boston and the Boston Society of Architects. The entry was originally published here.

Seaport is perhaps the most rapidly changing neighborhood in Boston. Once an industrial center, then a parking lot with harbor views, and today a burgeoning tech and innovation center, Seaport has had quite a tumultuous past. However, little evidence of these phases in the district’s history (despite their onetime dominance) appears on the streets of Seaport today. Still, one artifact remains. Just as it links Seaport to the Financial District, the Northern Avenue Bridge links Seaport to its past. The Union Freight Railroad once carried the spoils of the district, often seafood, to Downtown Boston and beyond. With Seaport undergoing rapid, dramatic development, it is time for the bridge to once again become a vital piece of Seaport commerce.

My proposal aims to recreate the commercial hub which the bridge once was, honoring its history and its connection to Seaport commerce while also creating a shopping destination for all residents (both new and longtime) of the district. To do this, the bridge should be repaired and become Bridge Market, a “fisherman’s market”. Of the three central passageways on the bridge, the outer two would become space for Seaport seafood vendors to set up shop. These vendors would serve Bostonians from food trucks, which could be driven off of the bridge every day to be resupplied. The central passageway would be left as an area for pedestrians to browse the market and make their way across the Channel. The market would look similar in form to a farmers market, such as the one at Dewey Square.

Through the vendors at Bridge Market, the entire Seaport district would be represented. Longtime local fisherman currently selling their daily catch at the Boston Fish Pier just a mile down Seaport Boulevard would be given another outlet to sell their seafood, and an opportunity to sell directly to the people of the District. Beloved Seaport seafood restaurants such as The Barking Crab and Yankee Lobster would also be given an opportunity to expand. Such businesses, facing the upheaval of new development, would be able to cement their place in the District, and in the process preserve the character of historical Seaport. For sale on the bridge could be both prepared food for lunch, dinner, or snacking, as well as unprepared food for people to bring home and cook themselves. Such a model worked well in New Bedford, where the Fisherman’s Market was a hit, providing office workers with fresh cod and shellfish to bring home to their families.

As Bridge Market, the Northern Avenue Bridge would serve as an iconic entrance to the Seaport district, similar to the Chinatown gate. Visitors to Seaport, with its unvaried and often uninviting steel-and-glass towers, will find an open, human-scale, and interactive contrast in Bridge Market.

Development in the past and present has left little room for the history of Seaport to endure. A “Fisherman’s Market” would prevent more of the classic Seaport from slipping away in the face of new development. Repurposed as Bridge Market, the Northern Avenue Bridge would become a destination where Seaport’s past and present meet and exist alongside each other in harmony. At Bridge Market, the seafood of Seaport’s past can live on through new favorite food trucks and vendors. Bridge Market would provide new opportunities for food trucks, already a huge hit around the city, to expand into a new sector. It would be the 19th and 20th century food of Seaport, presented through the 21st century style of service. As Bridge Market, the Northern Avenue Bridge would symbolize Seaport’s past, an ode to the fishermen and longtime seafood institutions of the South Boston Waterfront.

Bridge Market could be built in two different ways, depending on the expected number of vendors and the eventual budget. The first option would raise the bridge higher in order to accommodate the 16-foot height requirement; however, this could cause difficulty due to ADA requirements. The other option, which includes demolishing the two non-moving sections and replacing them with pedestrian bridges, could solve this accessibility problem but would leave less space for vendors. In order to make the correct decision on the design, cost and demand factors must be considered.

Preserving and revitalizing the Northern Avenue Bridge as Bridge Market could play an important role in preserving the industrial history of the Seaport District itself. As the Union Freight Railroad once linked Seaport and the Financial District through the transportation of goods in the 1800s, Bridge Market could do the same today.

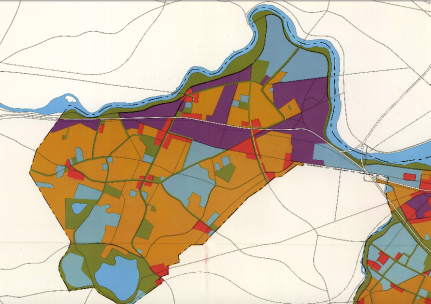

Following the model of the New Orleans Urban Water Plan and the “Making Room for the River” plan in the Rhine region, my proposal is for the accommodation of water in these two neighborhoods through the use of canals which will be designed to flood and let water in, not attempt to keep it out.

Following the model of the New Orleans Urban Water Plan and the “Making Room for the River” plan in the Rhine region, my proposal is for the accommodation of water in these two neighborhoods through the use of canals which will be designed to flood and let water in, not attempt to keep it out.